Amazon (AMZN: $1000/share) saw its stock jump by 3% Friday morning after it announced its intention to acquire Whole Foods Market (WFM) for $42/share. The acquisition represents a 27% premium to WFM’s closing price the day before and big win for activist hedge fund Jana Partners, which had been pushing for the high-end grocery chain to sell itself.

Based on AMZN’s share price gain, investors clearly think this deal is a winner for the e-commerce giant. While this deal certainly could be good for AMZN, we believe the market may be ignoring some of Whole Foods Market’s off-balance sheet liabilities that make this acquisition more expensive than it appears.

What is undoubtedly true is that this deal is terrible news for any company in the grocery business, as evidenced by the large drop in the stock prices of Kroger (KR), Target (TGT), Wal-Mart (WMT), and Sprouts (SFM).

Winner: Whole Foods Needed This Deal

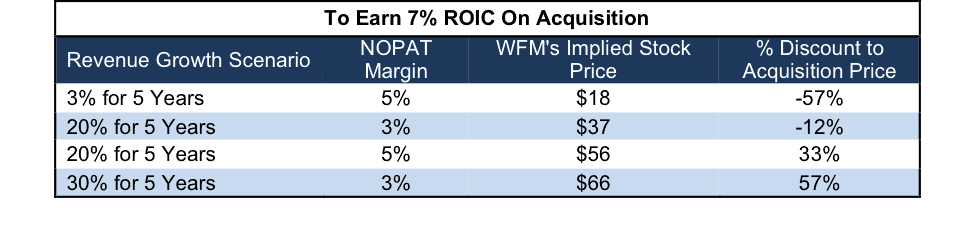

We have been bearish on Whole Foods for several years. In the past, the company had strong revenue growth but weak margins. As Figure 1 shows, that issue has become even worse in recent years, as revenue growth has slowed and operating profit (NOPAT) margins have worsened.

Figure 1: WFM Margins And Revenue Over The Past Decade

Before this merger was announced, WFM’s valuation had shrunk significantly. Its price-to-economic book value (PEBV) of just 1.1 suggested that the market expected the company to grow NOPAT by no more than 10% over the remainder of its corporate life.

Still, the trends in Figure 1 suggest that even those modest expectations would have been too much for Whole Foods to achieve. The company’s NOPAT declined by 8% in 2016 and has fallen 18% over the past twelve months. This buyout looks like a best-case scenario for WFM shareholders.

Loser: AMZN Investors: This Deal Is More Expensive Than It Appears

Most outlets covering this acquisition have slapped a $13.7 billion price tag on it, reflecting the $42/share offer plus roughly $1.2 billion in long-term debt and capital lease obligations. However, that number misses roughly $6 billion from the present value of future operating lease obligations.

Operating leases are a form of off-balance sheet debt that allow companies to bury significant amounts of invested capital in the financial footnotes. The real price Amazon is paying, accounting for both the cash portion of the deal and all assumed liabilities, is closer to $19.7 billion.

As it stands today, this deal would destroy value for Amazon shareholders. Based on Whole Foods’ 2016 NOPAT of ~$700 million, the deal has a return on invested capital (ROIC) of ~4%, well below Amazon’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC) of 7%.

However, this deal does have some obvious synergies and strategic growth opportunities. Whole Foods stores can double as warehouses, lowering Amazon’s shipping costs. 1/3 of all Americans with annual incomes over $100,000 live within three miles of a Whole Foods, making them ideal centers to reach high value customers.

On the flip side, Amazon’s brand name, technology, and delivery network could supercharge Whole Foods’ sales growth as it capitalizes on the growing market for at-home grocery delivery. Presumably, Amazon will absorb Whole Foods into its AmazonFresh service. It could also lower costs by automating checkout at the physical stores.

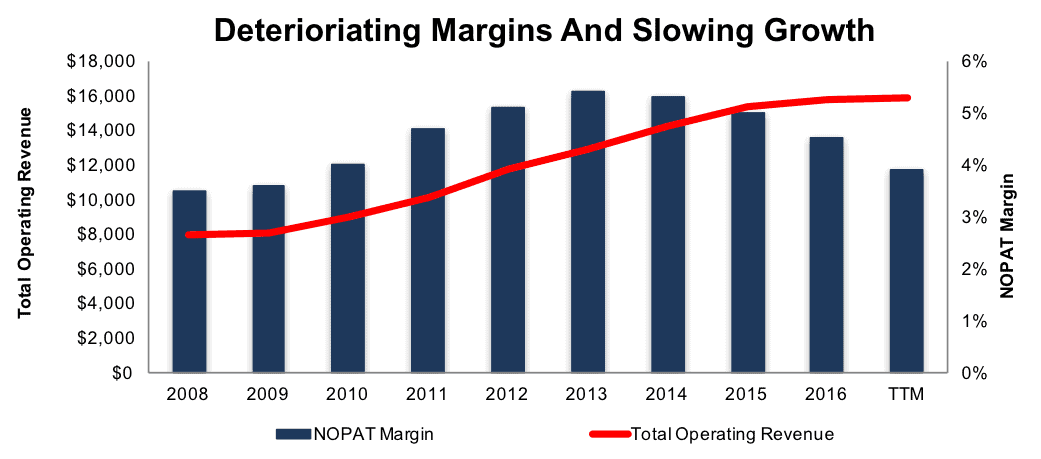

Given Amazon’s penchant for undercutting competitors, it’s unlikely that this deal will help Whole Foods’ margins, but the deal could still work. Figure 2 shows that, even with some margin compression, the deal could create value for Amazon shareholders.

Figure 2: WFM Valuation Scenarios

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings.

The math on acquisition analysis is very simple when eyed through the economic lens. For this deal to create shareholder value for Amazon, management must achieve synergies that translate into growing Whole Foods’ NOPAT by 95% (or nearly doubling it with any further capital investment). That kind of growth is a real challenge in the ultra-competitive grocery business, but it would allow Amazon to earn a 7% ROIC (equal to WACC) on the $19.7 billion acquisition of Whole Foods. Again, this deal is more expensive than investors think.

AMZN bulls deserve guidance from management as to how they will achieve that growth.

Figure 2 shows the valuation implications of a few other financial scenarios. For example, if Amazon can grow Whole Foods’ revenue by 30% compounded annually for the next 5 years with 3% NOPAT margins, it could afford to pay over $28 billion and still earn an ROIC equal to its WACC on the acquisition. On the other hand, if Whole Foods stays on its current growth and margin trajectory, the deal will end up destroying value at the current price.

Loser: Brick And Mortar Stores Continue To Get Pummeled

While this acquisition could go either direction for Amazon, it’s clearly bad for every other company in the grocery business. From day one, Amazon has focused on dominating every market it enters, even if it has to sacrifice profitability. That single-minded focus, combined with its technology and logistical capacity, threaten the margins and share of every other company in the industry.

The market clearly understands this strategy, as the grocery stocks were hit hard Friday. Kroger fell by 9%, Sprouts 6%, and Target and Wal-Mart both fell 5%. For the pure grocery chains, already beset by falling margins and the same slowing growth that plagued Whole Foods, it’s hard to see a bullish case.

The picture is more complicated for Wal-Mart and Target. Both companies earn razor thin margins on groceries and use them to attract customers into the stores, where they can then be persuaded to buy higher margin goods such as apparel, electronics, and furniture.

To combat Amazon’s push into groceries, these two retail giants will either need to find new ways to drive foot traffic or grow more competitive online. Alternatively, they could try to swoop in and buy Whole Foods themselves.

With WFM currently trading at ~$43/share, the market clearly sees potential for a bidding war. While it’s unclear if either Target or Wal-Mart could extract the same amount of value from Whole Foods as Amazon, either might find it worth overpaying just to keep it out of Jeff Bezos’ hands.

Of the two, Wal-Mart seems the more likely bidder. It has more resources, a recent history of acquisitions, and more to lose from Amazon’s push into groceries. Wal-Mart earns over 50% of its revenue from groceries, compared to just 22% for Target.

Of the two, Target is also significantly cheaper, with a price to economic book value (PEBV) of just 0.4, compared to 0.7 for Wal-Mart. We called Target the better stock to buy in January, and it’s still the better play for investors who want to buy the dip.

That said, it’s probably a better idea for investors to stay away from this sector altogether. Amazon is still richly valued even if this acquisition works out. Meanwhile, the brick and mortar stocks are cheap, but their business models are clearly under attack by a formidable adversary. There are other sectors with a more attractive risk/reward profile.

This article originally published on June 19, 2017.

Disclosure: David Trainer and Sam McBride receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, sector, style, or theme.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and StockTwits for real-time alerts on all our research.

Click here to download a PDF of this report.